A recap from the Whale Museum’s history: 1998

On June 17th 1998 the museum moved in a 200 m2 area in a old baiting shed by the harbor called „Verbúðir“. In the next years the museum gained more popularity as it dwelled in a good relationship with the neighbours who were mostly fish baiting workers.

Ágrip úr sögu Hvalasafnsins: 1998

Þann 17. júní Árið 1998 flutti safnið í um 200 m2 rými á efri hæð “Verbúðanna” við höfnina undir nafninu “Hvalamiðstöðin á Húsavík”. Gestafjöldi óx jafnt og þétt og samhliða því þörfin fyrir stærra húsnæði sem hentaði starfsemi safnsins betur.

Ágrip úr sögu Hvalasafnsins: 1997

Forveri Hvalasafnsins á Húsavík var lítil sýning í sal félagsheimilisins á efri hæð Hótels Húsavíkur sem opnaði árið 1997. Á þessum tíma voru áætlaðar hvalaskoðunarferðir í boði þriðja árið í röð frá Húsavík og fékk hótelstjóri staðarhótelsins Páll Þór Jónsson þá hugmynd að opna sýningu á hótelinu tileinkaða hvölum. Ásbjörn Björgvinsson var fenginn til að leiða verkið og flutti hann norður ásamt fjölskyldu sinni í janúar 1997.

Ásbjörn fór til Englands á Breska náttúrusögusafnið á fund Richard Sabin sýningarstjóra safnsins í þeim tilgangi að læra að verka af hvalbeinunum en þar er að finna stærsta beinagrindasafn heims. Richard Sabin hefur verið í tengslum við safnið og Húsavík allar götur síðan. Hann stjórnaði til að mynda aðgerðum við uppgröft hvalbeina á Keflavík á Ströndum árið 2001 en þeim fundi er gerð betur skil í einu af sýningarrýmum safnsins.

Richard

A recap from the whale museum’s history: 1992-1995

The Húsavík Whale Museum opened an anniversary exhibition in May 2019 to celebrate its 20th anniversary.

In the next weeks, some parts of the museum’s story will be reveiled here on the museum blog. We begin our journey in 1992 because as in all good stories there is always a preface behind it.

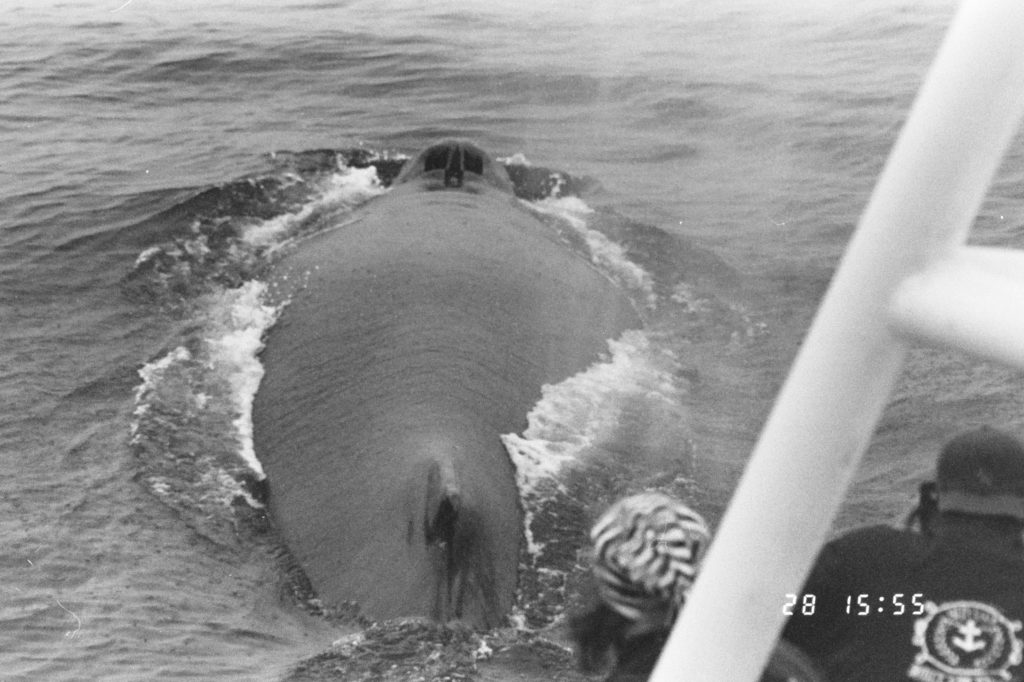

The origin of the Húsavík whale museum can be traced to whale watching tours that were operated in Höfn from 1992-1994 on the initiative of Discover the World. In the first trip were a british guide Mark Carwardine and Ásbjörn Björgvinsson which would later establish the Húsavík whale museum. The tours took about 8 hours. In 1994 scheduled whale watching tours in Húsavík were operated for the first time by the company Sjóferðir Arnars. In the following year a few groups arrived to Húsavik for whale watching, f.e. from Discover the World. Whale sightings had decreased in Höfn at the time but Húsavík which was known as an old minke whaling area had also its advantages for a whole lot shorter distances than the tours in Höfn‘s area. In 1995 a whale watching course was held in Keflavík where foreign speakers gave an inside knowledge about whale watching as a phenomenon. One of the speakers was Erich Hoyt. By the summer of 1995 two whale watching companies, North Sailing and Sjóferðir Arnars were opertaring from Húsavík harbor on a daily basis.

End of whale watching season 2019

Last Saturday was the final day of a 9 month long whale watching season in Húsasvík. Both Gentle Giants and North Sailing departed for their 30th and final tour of November but as a consequence of especially good weather in November, whale watching has been available every single day. According to recent update of Gentle Giants November 2019 was a month to remember. The bay was really active, with passengers gazing at as much as 30 humpback whales in the same tour as well as other species!

The Húsavík Whale Museum enjoyed a visit of over 31 thousand guests this season, a similar number of guests as in 2018. The museum was open every to from April 1st to October 31st. From November 1st and until March 31st the opening hours will be 10-16 on weekdays.

The museum’s employees are currently doing typical winter projects in maintenance, collection cataloguing, exhibition updates etc. etc.

Photo by: Christian Schmidt

Humpback whale – An introduction

Dear reader,

Whalecome at the introduction of the whales of Skjálfandi bay part 5. After the blue whale and the porpoise, the minke whale and the white-beaked dolphin lets introduce the humpback whale, the most commonly seen whale in Skjálfandi bay!

Latin name: Megaptera novaengliae

Common name: Humpback whale

Icelandic name: Hnúfubakur

Average

life span: 50 years

Diet: krill and small schooling fish

Size: 13 – 17 meters

Weight: 25-45 tonnes

Humpback whales are one of the largest whales, with males reaching lengths of 14 meters and females reaching lengths of 17 meters, about the size of a school bus. The pectoral flippers are a third of their body length and can reach the length of 6 meters. Humpback whales are active swimmers and can be seen breaching, tail slapping and flipper slapping. It is theorized that the breaching and tail/flipper slapping is a way of communicating with each other, but may also be used to show dominance and health during the mating season. Humpback whales also use vocalization to communicate with each other, males are known to sing during the mating season. A song can last up to 30 minutes and can be heard from over 30km away.

The year of the

humpback whale is split up in 2 sections feeding and breeding. During the

summer humpback whales can be found in colder nutrient rich waters like

Iceland, Norway and Canada, where they feed on krill. During the winter the

humpback whales can be found in warmer waters round the equator like the

Caribbean. Here the humpbacks mate and give birth. The gestation period of

humpback whales is 11 months. When a calf is born its 4,5 meters in size and

weighs 900kg. Calves can drink up to 600L milk per day. Mother and calf

communicate with each other through by whispering, this is so that they cannot

be overheard by predators such as orca´s (killer whale).

Humpback whales are baleen whales and thus use filter feeding to feed. Humpback

whales are known to use several techniques to feed, one of these techniques is

bubble net feeding. With bubble net feeding a humpback whale blows air from the

blow hole trapping the fish and krill to the surface and then feeds on the fish

and krill. Humpback whales dive on average round 5 to 10 minutes, but up to 40

minutes has been recorded. When humpback whales are travelling the swim between

5-15 km/h, when feeding they slow to a 2-5,5 km/h, the max speed they can reach

is 25km/h.

Humpback whales can be seen in Skjálfandi Bay for a great majority of the year, though their prime season is in the summer months.

White beaked dolphin – An introduction

Dear reader,

Whalecome at the introduction of the whales of Skjálfandi bay part 4. After the blue whale, the porpoise and the minke whale lets introduce the white-beaked dolphin!

Latin

name: Lagenorhynchus albirostris

Common name: White-beaked

dolphin

Icelandic name:

Average life span: 30 – 40 years old

Diet: Fish, crustaceans and cephalopods

Size: 3.1 meters

Weight: 180-350kg

White-beaked dolphins are endemic to the North Atlantic ocean. They can

only be found from the north east coast of America and the north west of Europe

up to Spitsbergen. White-beaked dolphins are very social, they live in groups

called pods from 5 to 50 dolphins, during certain social aggregations these pods

can contain over 100 or even 1000 dolphins. White-beaked dolphins are also

known to have all male pods called ´alliances´ and all female pods called ´parties´.

They are fast swimmers they can reach speeds of 45km/h. When they are

travelling at speed they sometimes jump.

White-beaked dolphins reach sexual maturity round the age of 7, breeding season

is from May through September. The gestation period is 11 months, when the

calves are born they are 1 meter long and weigh 40kg.

Young white-beaked dolphins love to play in the wake of boats and larger

whales. They like it so much that they can even harass whales to swim faster so

they can play in the wake.

Each dolphin has a slightly different tone range, from which other dolphins can

understand who said something through clicks and whistles.

White-beaked dolphins stay in Skjálfandi bay throughout the year. During the summer months it is possible to see mother and calf pairs.

The Minke Whale – An Introduction

Dear reader,

Whalecome at the introduction of the whales of Skjálfandi bay part 3. After the blue whale and the porpoise lets introduce the minke whale!

Latin name: Balaenoptera acutorostrata

Common name: Minke whale

Icelandic name: Hrefna

Average

life span: 50

years

Diet: krill and small fish

Size: 6 – 10 meters

Weight:

10

tons

Minke whales are one of the smallest of the baleen whales. There are two different species of minke whales, the common (northern) minke whale and the Antarctic (southern) minke whale. The northern minke whale can be found round Iceland.

Minke whales, like other baleen whales, use the filter feeding technique to feed. Minke whales mostly live individually. The max speed for minke is 40km/h, on average they swim between 5-25 km/h. Minke whales have one predator, groups of orca´s (killer whales). The chases of Orca´s and minke whales can last up to 1 hour. Minkes are known by some people as stinky minke, due to their bad breath, when you are close to a minke and it breaths out you can smell the breath. The dive times of minke whales are up to 20 minutes, on average 3- 5 minutes. Minke whale do not show their tail (fluke) when they go for a dive.

Minke whales become sexually mature at the age of 6, like most baleen whale minkes migrate at the end of summer to warmer waters in the south (near the equator). Here they mate and give birth, the gestation period of minke whales is 10 months. When the calf is born its 2,5 meters long and weighs 450 kg. In 6 months they have doubled in size.

Unfortunatly minke whales are one of the whale species that is still being hunted by Japan. The japanese government has allowed for 52 minke whales to be hunted in 2019. The Antarctic minke whale has the status of near threatened according to IUCN red list.

Minke whales in Skjálfandi bay can be seen throughout the year in Skjálfandi, however the chance are getting smaller. This is because warming of the sea waters which causes the prey of the minkes to move further north, which means that the minkes followed their prey.

Increase in July’s visitor numbers

The number of visitors in the Húsavík Whale Museum were close to 10 thousand in July. That’s an increase from 2018 and a little bit more than in the same month in 2017. Germans, Americans and French are the most frequent visitors.

This year’s increase of visitors to the museum in July is a very positive and even surprising news. In the aftermath of WOW Air’s collapse earlier this year, a number of forecasts assumed decreation of tourists in Iceland – especially outside the Reykjavík area. With that in mind, any news in the opposite direction is something to cheer about even though the visitor numbers of the Húsavík Whale Museum can’t be transferred to the overall numbers.

Gestafjöldi í júlí fram úr væntingum

Gestir Hvalasafnsins á Húsavík í júlí 2019 voru tæpir 10 þúsund talsins. Það er fjölgun upp á rúm 11% frá árinu 2018 og ívið fleiri en heimsóttu safnið í júlí 2017. Þjóðverjar og Bandaríkjamenn eru áfram fjölmennir sem hlutfall af heildargestafjölda en þá hefur einnig verið góð aðsókn frá mörgum Mið-Evrópuríkjum, ekki síst Frakklandi.

Þessi fjölgun gesta á háannatímanum verður að teljast afar ánægjuleg og jafnvel óvænt tíðindi fyrir Hvalasafnið. Í kjölfar tíðinda um fall WOW Air síðastliðið vor þótti líklegt að mikil fækkun yrði á komum ferðamanna til landsins og myndi það koma illilega niður á landsbyggðinni. Það er því afar gleðilegt að upplifa vísi af því að ferðamönnum fækki ekki, enda þótt ekki sé hægt að heimfæra gestafjölda Hvalasafnsins yfir á heildarfjölda ferðamanna sem heimsækja Norðurland.